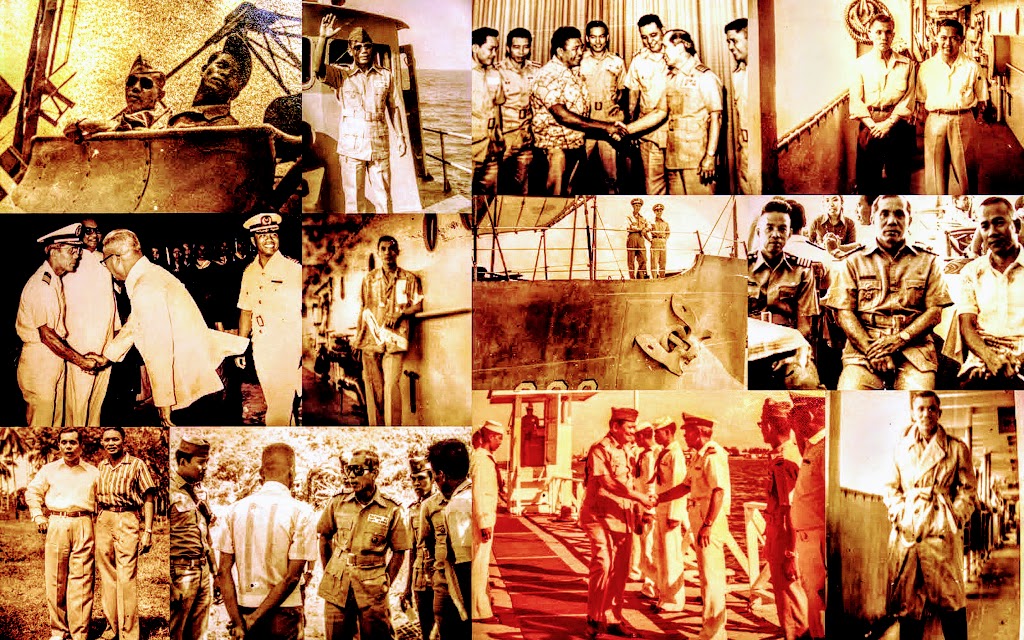

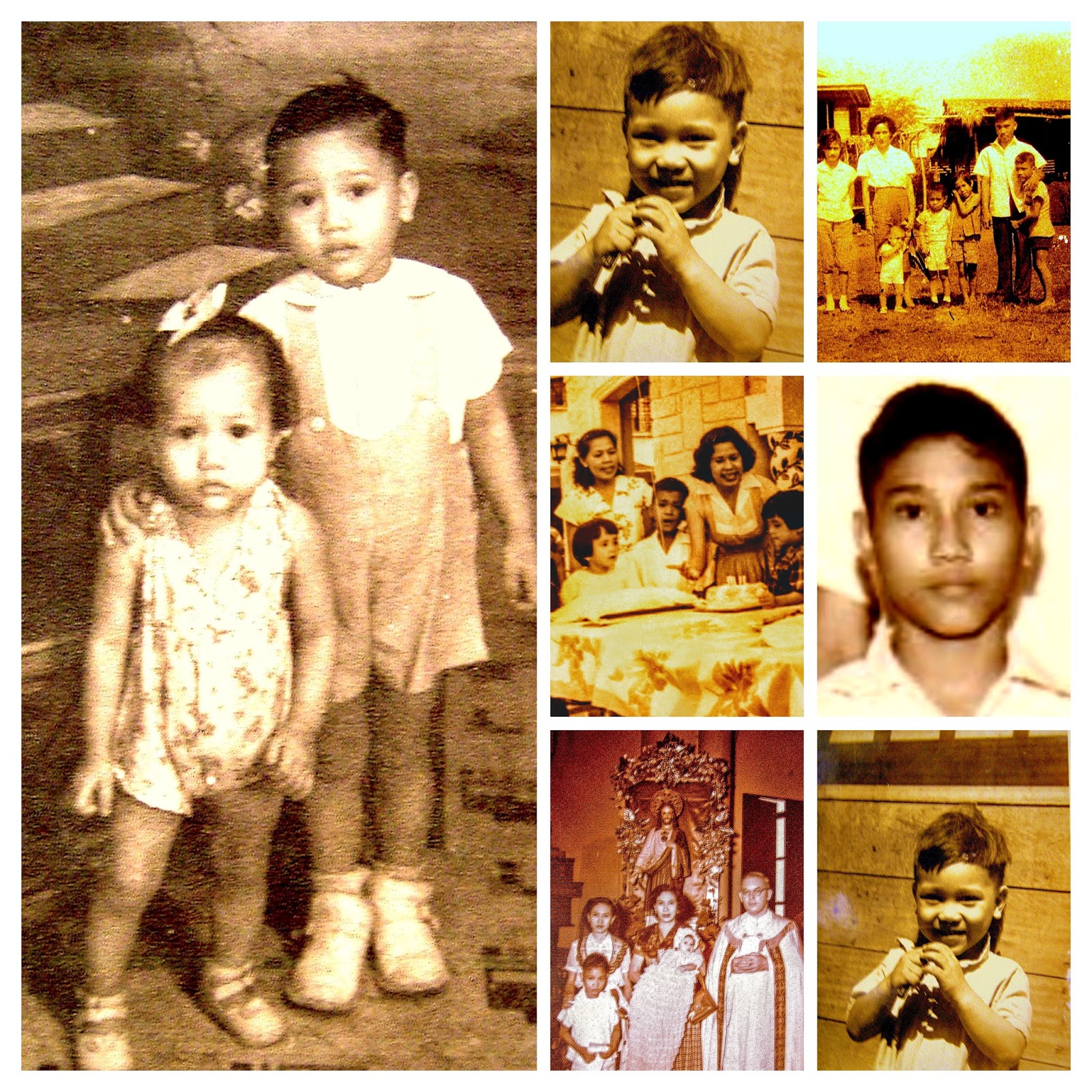

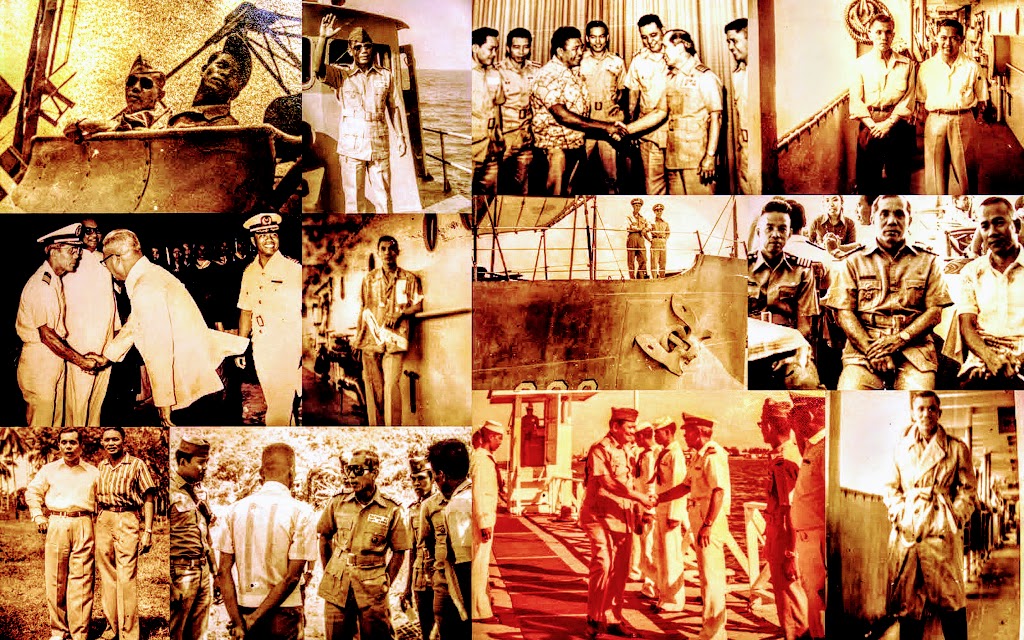

Papa and his various duty assignments in the 60's who left our midst Feb. 2010. Early in his career as a naval officer, seldom we see him for a decade as he was out to the Southern seas in Mindanao fighting the banditry and secession movements of the Moros. He will go on to higher positions, to take command of his own ship, then a number of ships as a task force commander, then Chief of Staff of the Philippine Coast Guard, a professor in academia at the National Defense College of the Philippines, Dean at the Command and General Staff College, a base commander at the Manila Naval Station and Cavite Naval Base at Sangley Pt. But what I remember most was him on the bridge of RPS 1133, and I a pre school kid, looking at a young Lt. taking his ship out to the open seas, out of Manila Bay.

Papa and his various duty assignments in the 60's who left our midst Feb. 2010. Early in his career as a naval officer, seldom we see him for a decade as he was out to the Southern seas in Mindanao fighting the banditry and secession movements of the Moros. He will go on to higher positions, to take command of his own ship, then a number of ships as a task force commander, then Chief of Staff of the Philippine Coast Guard, a professor in academia at the National Defense College of the Philippines, Dean at the Command and General Staff College, a base commander at the Manila Naval Station and Cavite Naval Base at Sangley Pt. But what I remember most was him on the bridge of RPS 1133, and I a pre school kid, looking at a young Lt. taking his ship out to the open seas, out of Manila Bay.

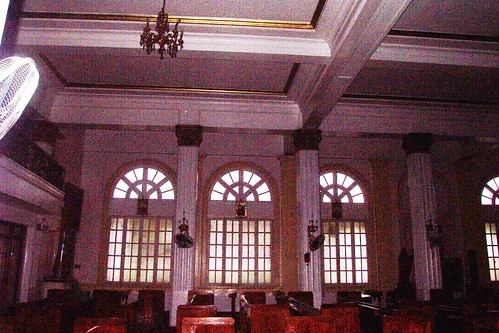

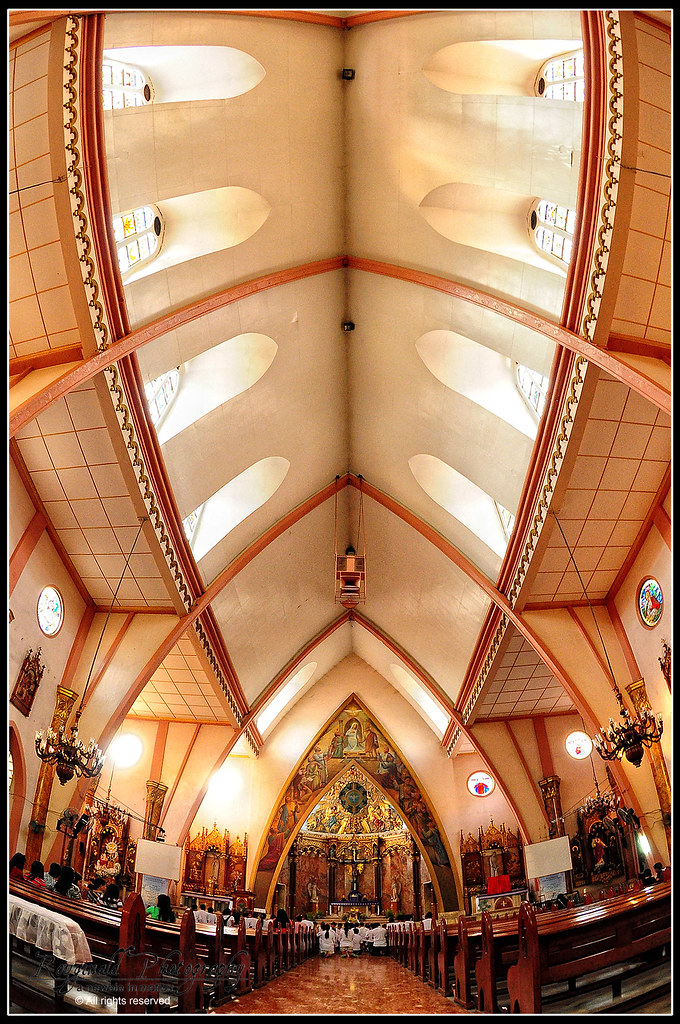

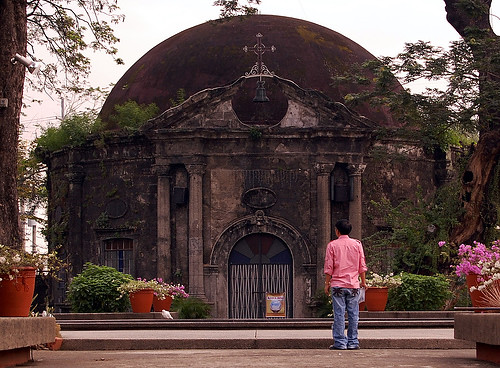

Ramparts of Fort San Antonio Abad where the old HQ of MNS was an addendum perched on top. The old building is gone but the fort remains in its original grandeur.

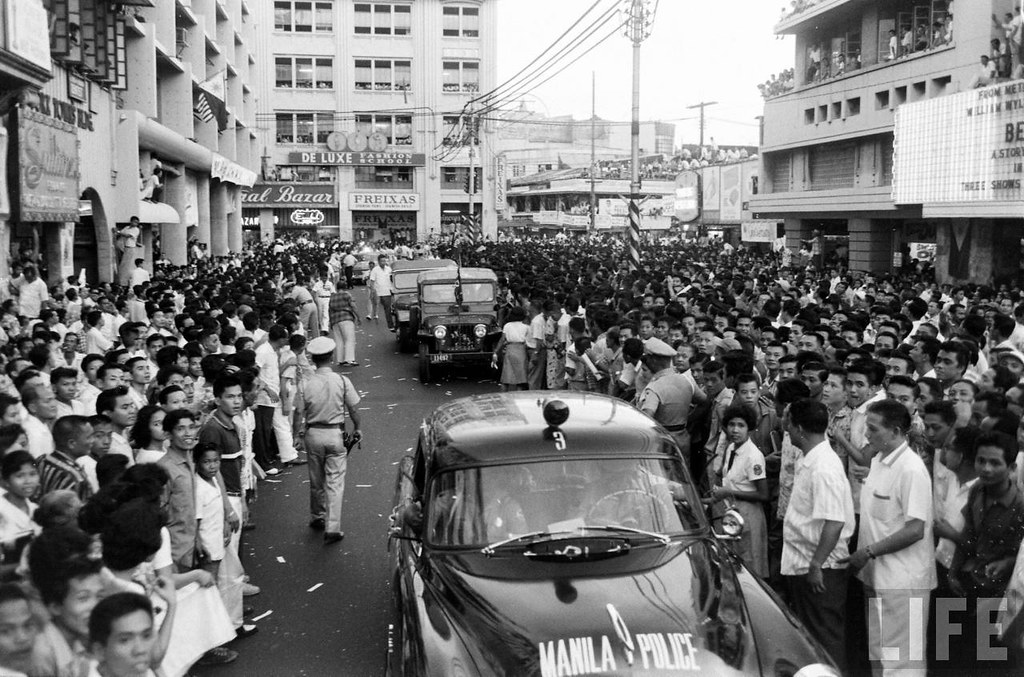

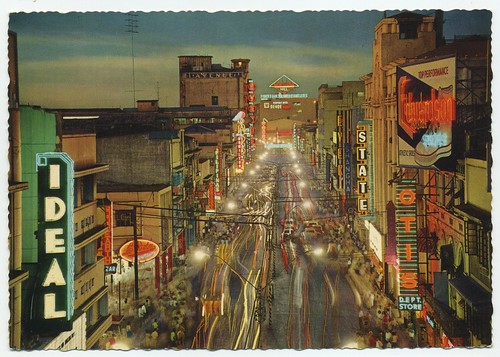

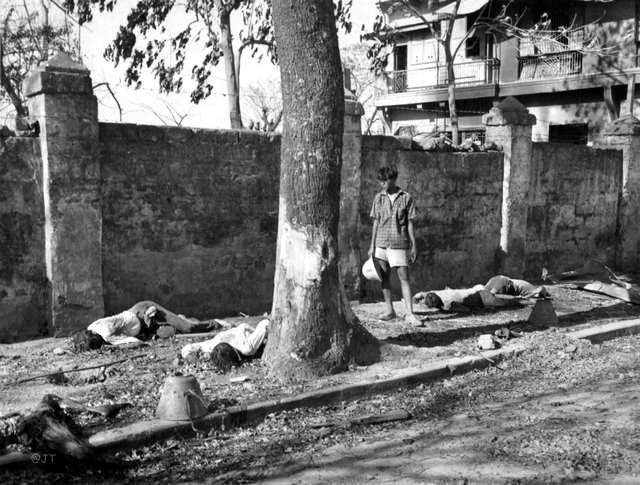

February 9, 1945. Colorado Street, Ermita, Manila. Photo:

Prized by the U.S. for its strategic location in the Pacific Ocean, and forming what MacArthur called "a key or base point of the U.S. defense line," the Philippines presents a natural barrier between Japan and the abundant resources of East and Southeast Asia. An archipelago comprising over seven thousand islands, the Philippines is situated east of Vietnam, approximately seven hundred miles from Formosa, Taiwan. With a tropical-marine climate and a land area of 115,124 square miles, the Islands were awarded to the U.S. in 1898, at the conclusion of the Spanish-American War.

A year after acquiring the Philippines in 1898, America instituted a system of self-governance in the Islands to grant the Filipinos political experience and eventual independence. This experiment limped along, because U.S. intervention never truly ceased. Filipinos were allowed participation in the administration of the Philippines, but U.S. citizens retained all the substantial policy-making positions.

In 1935, the Philippines gained Commonwealth status under President Manuel Quezon, though it remained in every respect a U.S. colony, with Douglas MacArthur serving as Military Advisor to President Quezon and field marshal of the Philippine Army prior to the outbreak of WWII (1935-1941). Under American colonial rule, the objective was the "political education on democratic government" of the Filipinos, along with economic preparation for complete independence; however, this was primarily a farce, and dialogue of independence was biased with an eye towards preserving American self-interests and Philippine dependency upon the U.S. For example, constitutional provisions, such as the Public Land Act, limited the exploitation of Philippine lands and other natural resources to Philippine and American citizens. The inclusion of Filipino interests in the Public Land Act was meant to pacify the elite classes and garner their support for continued American occupation. From the point of view of Japan's Imperial Government, the Public Land Act translated to a slight against Japanese nationals, because it essentially disenfranchised over twenty thousand Japanese who were residing in the Philippines by 1935. Such policies were aimed at bolstering U.S. economic interests in the Philippines.

By 1941, Japan was blistering from several perceived U.S. insults. Its oil inventories were in dire straits due to American-led global oil embargoes. For the Japanese Government, which had been suffering severely from fuel shortages, the Philippine sugar fields represented the potential for an alternative alcohol fuel source and butane for aviation fuel. The need for substitute fuel sources had hit a critical stage if Japan were to sustain the war effort. At stake in the Philippines were vast natural resources in the form of rice, coconut, sugar cane, hemp (locally known as abaca), timber, petroleum, cobalt, silver, gold, salt, and copper--export industries which were thriving thanks in large part to the generous introductions of American capital.

Japan also viewed the Philippines as a golden opportunity for retribution against the U.S. for the pervasive disenfranchisement policies it promoted in the Philippines, and the prohibitions it championed against Japan globally. As an added bonus, Japan recognized that its occupation of the Philippines would deal America a grave economic blow, since the U.S. imported the bulk of its rubber, sugar, and various agricultural products from the Philippines.

It cannot be ignored that the Philippines was a logistical trading hub, since the Islands were advantageously located in close proximity to the South China Sea, Philippine Sea, Sulu Sea, Celebes Sea, and the Luzon Strait. This was a fact of which both Japan and the U.S. were keenly aware. From the Japanese perspective, its invasion of the Philippines served multiple purposes: it was a blatant affront meant to humble the U.S. and impress upon the Americans the sheer might and cunning of the Japanese military; and, by 1941, the Philippines was a trophy ripe for the picking. For nearly half a century, the Commonwealth had thrived under the protection of the powerful United States of America. What is more, by the outbreak of WWII, the Philippines had benefited economically from its colonial ties to the U.S. for many decades. This had guaranteed a measure of stability and lawfulness, with corruption kept at a minimum, which in turn fostered a climate of legitimacy that attracted private enterprises to the archipelago. Because of the inflow of U.S. financial subsidies into its military infrastructure, the Philippines possessed a fairly modern string of tactically placed naval bases, airstrips, oil tank fields, and roadways that wound through the Island from Cavite to Cebu, from Zambales to Manila--fortifications that the Japanese coveted.

For Japan, the Philippines was too tempting a prize to resist. On December 8, 1941, Japan launched its "onslaught against the Philippines" within twenty-four hours of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The United States Government representatives in the Philippines reacted swiftly, interring Japanese nationals residing in the Commonwealth. Japanese consulates, Japanese schools and office buildings were converted into temporary detention camps. But America's grip upon the Philippines was tenuous at best. The combined forces of MacArthur and the Philippine Army were woefully outmanned, and could not repel the full-scale Japanese assault. As a result, the internment of Japanese nationals proved to be short-lived, for scarcely two weeks later, the Japanese Army seized control of Mindanao in the southeastern Philippines, and all internees were released.

In an effort to rescue Manila from further destruction, on December 26, 1941, Douglas MacArthur declared Manila an "open city," before retreating and abandoning all defensive efforts. It was a calculated move intended to preserve Manila's historical landmarks and spare its civilians. This strategy was effective, and damage to infrastructure was minimal, since the incoming Japanese forces, for the most part, had respected wartime protocols. Soon after the Japanese took possession of Manila in January 1942, life continued on as before and a sense of normalcy gradually returned to the city.

Following MacArthur's retreat, while American and Filipino POWs were staggering across Mariveles on the southern end of the Bataan Peninsula in what came to be known as the infamous Bataan Death March, thousands of American civilians were imprisoned in internment camps in Manila. The U.S. internees in the Philippines represented the largest group of American civilians to experience "enemy occupation" during WWII.

During the early years of the occupation, the University of Santo Tomas internment camp was not much of a prison; internees were granted "passes" to visit family on the outside. Some passes were a month long, requiring only periodic check-ins. This changed as the war progressed and Japanese camp administrators grew increasingly fearful of subversives.

The Japanese tried very hard to win over the Filipinos. However, they did not tolerate dissention. If a household was caught with a short wave radio, which were forbidden, it was not uncommon for violators to be hauled off to Fort Santiago, an old Spanish fortress at the entrance of the Pasig River, never to be seen again. Discipline was rigorously enforced by the High Command. The Japanese officers disliked lawyers; they did not tolerate arguments, and demanded strict obedience from military and civilian subordinates. Generally, as long as the populace cooperated with officials, the Japanese treated Filipinos fairly and were respectful of local customs and traditions.

From an economic perspective, the Imperial Government recognized that its conquest of the Philippines placed into Japan's possession an agricultural country that could be brought to self-sufficiency, with minimal economic dependency. In its occupation of the Philippines, Japan gained numerous agricultural resources, including Manila hemp (abaca), which was used for rope and twine and was highly prized by the Japanese. An added windfall to Japan was that it had managed to deprive the U.S. and much of Europe of major sources of rubber, sugar, hemp, and coconut oil. Moreover, the Philippines was also expected to solve Japan's shortages in cotton and aviation fuel, by utilizing "chemical-yielding plants" like sugar cane and castor oil as alternative fuel sources. The goal was that the conversion of sugar to fuel alcohol as a substitute for gasoline, would appease Japan's fuel crises, while launching the Philippines into total fiscal self-sufficiency.

A popular theory is that WWII was a War of Annihilation, the Annihilation premise being that "civilians are military targets and not immune from warfare." This concept stretches the battlefield to encompass towns and private citizens, exterminating enemy populations and destroying resources (such as infrastructure), by brute force. This was not the case with the Japanese occupation in WWII in the Philippines. On the contrary, the situation began to deteriorate two years after the Battle of Midway, as the defeat at Midway slowly shifted the tides in the Pacific against Japan. With each mounting loss, the inhumane treatment of citizens in Japan's occupied territories escalated.

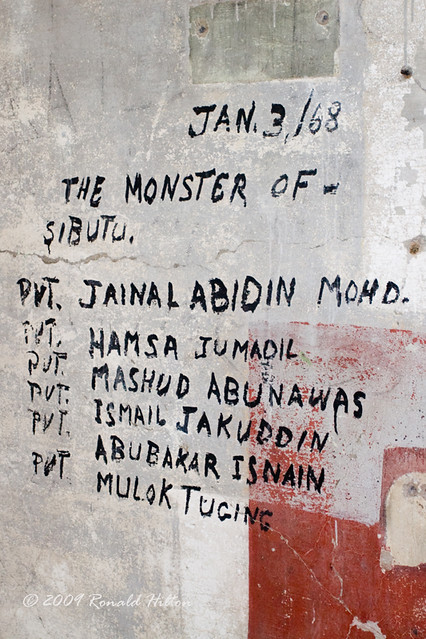

It was only towards the latter part of the Japanese occupation (very late in 1944), as American forces were steadily advancing across the South Pacific, that the hypothesis that Japan had unleashed annihilation tactics upon the Philippines, may hold any merit. By the time the sacking of Manila transpired on the eve of the American-led liberation of the Philippines in February 1945, the Japanese Imperial Army occupiers had been replaced by the Japanese Marines.

There were two Japanese contingents occupying the Philippines during this crucial time: the Imperial Army led by General Tomoyuki Yamashita, and the Japanese Navy (Marines) commanded by Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi. The initial occupation of the Philippines in 1941 was carried out by the forces of the Japanese Imperial Army (Yamashita's men), who were tasked with setting up a government in Manila, and assimilating the local population. It was a commission that for the most part, the Imperial Army conducted with self-restraint and discipline. Yet by the latter part of 1944, the majority of Imperial Army officers, whose soldiers had previously displayed a respectful tolerance of the local populace, who had shown a surprising fondness for children, and who had honored Filipino traditions, had gradually been replaced by the Japanese Marines. The Marines were comprised of Korean and Formosan forces and battle-hardened veterans of the vicious China Campaign. These men were charged with defending Manila against the invading Americans in 1945, as the Japanese Army retreated.

It was unfortunate that the Japanese contingent tasked with holding Manila were a different breed; they were seasoned veterans, desensitized by the brutality of previous campaigns. These Marines spared the Filipinos no mercy. As Japanese defeat loomed, the lines between civilian and military targets evaporated, and annihilation began. Where the Japanese had once been "instructed by their High Command to behave and set an example," irrationality reigned and "they behaved like animals." In a 1946 interview, Major General Charles A. Willoughby (U.S. Army, who served as Douglas MacArthur's Chief of Intelligence), confirmed that the sacking of Manila "was an unnecessary act of fury and brutality" that was carried out "mostly by men from the Japanese Marines, the remaining personnel of sunken ships, the commercial crewmen, and others. The army had retreated towards the hills."

In what came to be known as the Battle of Manila, the Marines spared no compassion as impending defeat translated to sanctioned brutality. As American bombs began to rain down upon the Islands, the Japanese Marines turned savage. There were numerous accounts of babies being tossed in the air and speared on bayonets. Sons were shot in front of their pleading mothers. Those who elected to remain outside the confines of religious institutions or were not interred at the camps, were rounded up by the Japanese in abandoned apartment buildings and houses and burned alive. Women, children, and the elderly were not spared. Anyone who attempted escape by climbing out of windows or scaling walls, were picked off by rifle fire like pigeons in a hunt.

"My Last Farewell"

Farewell, my adored Land, region of the sun caress'd,

Pearl of the Orient Sea, our Eden lost,

With gladness I give thee my Life, sad and repress'd;

And were it more brilliant, more fresh and at its best,

I would still give it to thee for thine welfare at most.

On the fields of battle, in the fury of fight,

Others give thee their lives without pain or hesitancy,

The place matters not: cypress, laurel, or lily;

Scaffold, open field, conflict or martyrdom's site,

It is the same if asked by home and Country.

I die as I see tints on the sky b'gin to show

And at last announce the day, after a gloomy night;

If you need a hue to dye your matutinal glow,

Pour my blood and at the right moment spread it so,

And gild it with a reflection of your nascent light!

My dreams, when scarcely a lad adolescent,

My dreams when already a youth, full of vigour to attain,

Were to see thee, Gem of the sea of the Orient,

Thy dark eyes dry, smooth brow held to a high plane

Without frown, without wrinkles and of shame without stain.

My life's fancy, my ardent, passionate desire,

Hail! Cries out the soul to thee, that will soon part from thee;

Hail! How sweet 'tis to fall that fullness thou may acquire;

To die to give thee life, 'neath thy skies to expire,

And in thy mystic land to sleep through eternity!

If over my tomb some day, thou wouldst see blow,

A simple humble flow'r amidst thick grasses,

Bring it up to thy lips and kiss my soul so,

And under the cold tomb, I may feel on my brow,

Warmth of thy breath, a whiff of thy tenderness.

Let the moon with soft, gentle light me descry,

Let the dawn send forth its fleeting, brilliant light,

In murmurs grave allow the wind to sigh,

And should a bird descend on my cross and alight,

Let the bird intone a song of peace o'er my site.

Let the burning sun the raindrops vaporise

And with my clamour behind return pure to the sky;

Let a friend shed tears over my early demise;

And on quiet afternoons when one prays for me on high,

Pray too, oh, my Motherland, that in God may rest I.

Pray, thee, for all the hapless who have died,

For all those who unequalled torments have undergone;

For our poor mothers who in bitterness have cried;

For orphans, widows and captives to tortures were shied,

And pray too that thou may seest thine own redemption.

And when the dark night wraps the cemet'ry

And only the dead to vigil there are left alone,

Disturb not their repose, disturb not the mystery:

If thou hear the sounds of cithern or psaltery,

It is I, dear Country, who, a song t'thee intone.

And when my grave by all is no more remembered,

With neither cross nor stone to mark its place,

Let it be ploughed by man, with spade let it be scattered

And my ashes ere to nothingness are restored,

Let them turn to dust to cover thy earthly space.

Then it matters not that thou should forget me:

Thy atmosphere, thy skies, thy vales I'll sweep;

Vibrant and clear note to thy ears I shall be:

Aroma, light, hues, murmur, song, moanings deep,

Constantly repeating the essence of the faith I keep.

My idolised Country, for whom I most gravely pine,

Dear Philippines, to my last goodbye; oh, harken

There I leave all: my parents, loves of mine,

I'll go where there are no slaves, tyrants or hangmen

Where faith does not kill and where God alone doth reign.

Farewell, parents, brothers, beloved by me,

Friends of my childhood, in the home distressed;

Give thanks that now I rest from the wearisome day;

Farewell, sweet stranger, my friend, who brightened my way;

Farewell to all I love; to die is to rest.

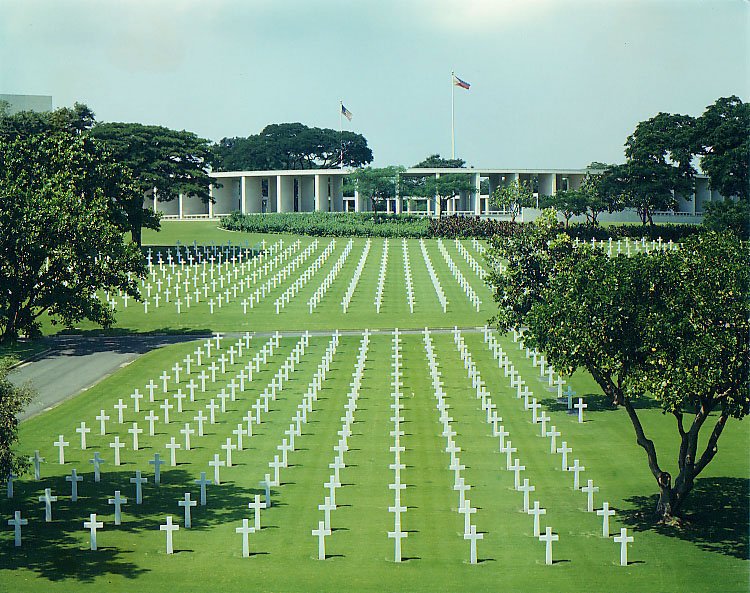

Rizal Park, Ermita. At the centre of it all is the 1913 bronze Rizal's monument situated a few metres away from the marker indicating the actual execution site. An honor guard is on duty 24 hours a day. Behind the monument, the original Spanish version of the poem "Mi Ultimo Adios" is engraved, along with translations in other languages. Rizal wrote this poem while imprisoned in his cell in Fort Santiago from November 3, 1896 to December 29, 1896. Many national dedication days are held in front of the Rizal monument. It is also where foreign leaders attend wreath-laying ceremonies during state visits.

Located on the monument is the statue of the national hero, but also his remains. On September 28, 1901, the United States Philippine Commission approved Act No. 243, which would erect a monument in Luneta to commemorate the memory of Jose Rizal, Philippine patriot, writer and poet. The committee formed by the act held an international design competition between 1905–1907 and invited sculptors from Europe and the United States to submit entries with an estimated cost of 100,000 peso’s using local materials.

| |

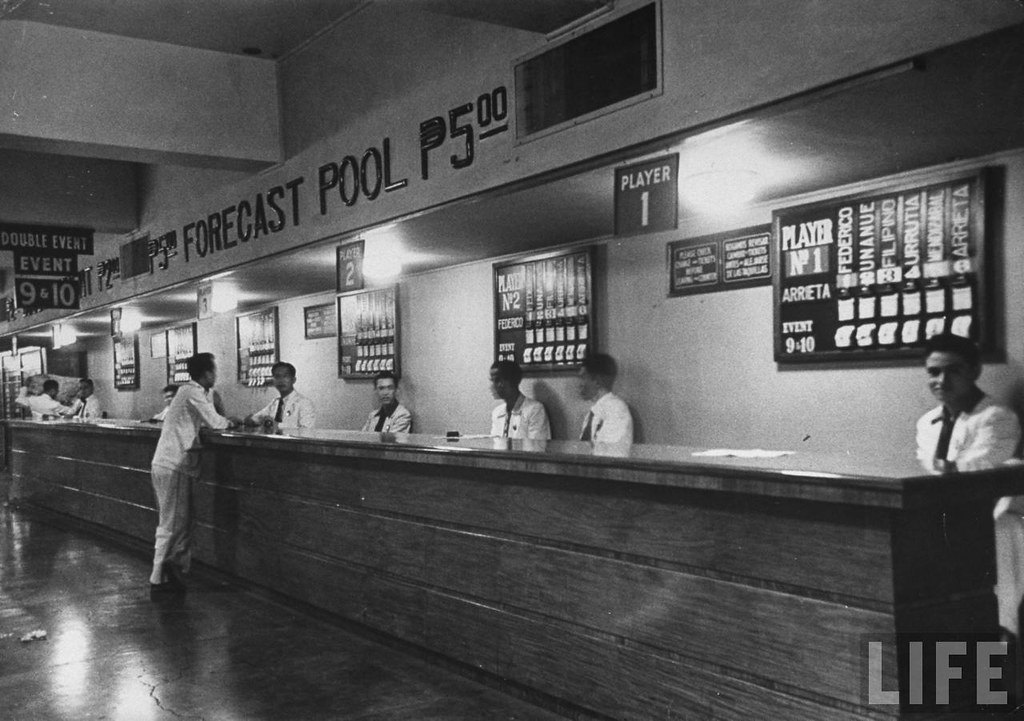

Sangley Point My father became the CO of Sangley Point Cavite Naval Base in the 70’s.

1960-photo

Ayuntamiento Building, Intramuros, Manila

Papa in the 60's as Commanding Officer(CO) MNS, extreme left Cdr. Oscar L. Tempongko

A big coastal gun is fired from fortified American positions on Corregidor Island, at the entrance to Manila Bay on the Philippines, on May 6, 1942. (AP Photo) #

Japanese forces use flame-throwers while attacking a fortified emplacement on Corregidor Island, in the Philippines in May of 1942. (NARA) #

Billows of smoke from burning buildings pour over the wall which encloses Manila's Intramuros district, sometime in 1942. (AP Photo) #

American soldiers line up as they surrender their arms to the Japanese at the naval base of Mariveles on Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines in April of 1942. (AP Photo) #

Japanese soldiers stand guard over American war prisoners just before the start of the "Bataan Death March" in 1942. This photograph was stolen from the Japanese during Japan's three-year occupation. (AP Photo/U.S. Marine Corps) #

American and Filipino prisoners of war captured by the Japanese are shown at the start of the Death March after the surrender of Bataan on April 9, 1942, near Mariveles in the Philippines. Starting from Mariveles on April 10, some 75,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war were force-marched to Camp O'Donnell, a new prison camp 65 miles away. The prisoners, weakened after a three-month siege, were harassed by Japanese troops for days as they marched, the slow or sick killed with bayonets or swords. (AP Photo) #

American prisoners of war carry their wounded and sick during the Bataan Death March in April of 1942. This photo was taken from the Japanese during their three year occupation of the Philippines. (AP Photo/U.S. Army) #

|

|

MNS nowJose V. Andrada Naval Station Manila, Philippines.

MNS nowJose V. Andrada Naval Station Manila, Philippines.

![Atty. Diosdado Macapagal raises the Philippine flag at Turtle Islands.<br />The caption reads:<br /><br />Atty. Macapagal got his first break as a public figure in 1948 when Vice President Quirino, then concurrently Secretary of Foreign Affairs, appointed him as Assistant Chief of its Law Division and assigned him to negotiate the return of the administration of the Turtle Islands from the United Kingdom to the Philippines. He succeeded and [Vice President] Quirino gave him the privilege of raising the Philippine flag over the islands. <br />- From Nipa Hut to Presidential Palace by Diosdado Macapagal<br />](http://25.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_maw980UQkV1qifq8yo1_500.jpg)

……………

……………